Home care workers (HCWs) are one of the fastest growing professions in the United States. Patients increasingly prefer to receive healthcare services in their own homes rather than at long-term care facilities. In addition to family caregivers, HCWs provide the instrumental and assistive care necessary to make home-living possible. Despite their importance, HCWs, who are mostly middle-aged women of racial and ethnic minority groups, are at the bottom of the healthcare hierarchy, earning dismally low wages and taking on multiple jobs to make ends meet. HCWs perform an essential and challenging job but feel under-appreciated and under-supported.

One reason HCWs are under-supported is that they do not work in a traditional clinical or office environment. Instead, they work alone in patients’ homes and often feel isolated and left to face the challenges of the job alone. In other professions, access to professional peers is an important support structure for getting work done. You might rely on peers to answer questions about how to do critical but non-explicit parts of the job. Seniors could mentor newcomers to help them learn the ropes. Peers can set the tone of the workplace, and you might rely on them for emotional support, as they can truly empathize with the challenges around the work. HCWs typically have had few opportunities to build those peer relationships in-person, a problem only worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

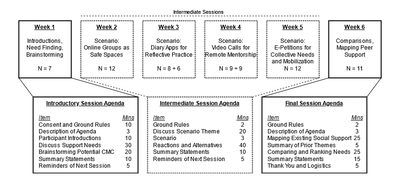

In this research, we wanted to understand how computer technologies could be designed to foster peer support for home care workers, in two questions. The first question was to understand the different peer support needs that HCWs had. We held discussion groups with 18 HCWs working in New York City and asked them to describe the types of support they currently received from other HCWs, why that support was valuable to them, and what kinds of support they wish they had. Secondly, we worked with those same HCWs to explore potential designs for technology-enabled peer support over several weeks. These discussions were focused around pre-recorded scenarios that described HCWs interacting with hypothetical technologies designed for different types of support.

For our participants, we found that three types of peer support stood out. The first is that mentorship was an important way to help teach newcomers about the home care job. Entering a patient’s home for the first time and being held responsible for their health is a daunting prospect. There are also many interpersonal and tacit aspects of care work that are difficult to learn with limited training. Some larger agencies had mentorship programs that enabled more experienced HCWs to support newcomers with on-the-job learning.

Secondly, because care work can be emotionally challenging, we found that HCWs relied on their peers to help them through the emotional labor they performed on the job. Participants described calling peers who could provide emotional support and help them stay calm in the face of emotional anxiety, distress, or pain. Peers were also valuable because they could empathize with and understand HCWs’ experiences and draw upon their own experiences to provide advice for how to address tricky interpersonal challenges in the patients’ homes.

Finally, the most one of the most surprising roles that participants assigned peers was as advocates for the home care profession. HCWs felt that their job was frequently misunderstood and dismissed as unskilled, domestic labor. This negative perception fed into the conflicts that HCWs had with patients and other healthcare professionals who might expect them to do housekeeping tasks and discount HCWs’ expertise. Participants felt an important role of peers was to help combat these perceptions by setting consistent norms and expectations around their practice and professional conduct, both with new HCWs and patients, and by encouraging knowledge growth. By sharing tacit knowledge and best practices and encouraging peers to seek additional training, participants hoped that HCWs could build a body of expertise that would be distinctly recognizable as belonging to the home care profession.

This deeper understanding of what HCWs value from peer support is a good starting point for designing technology that can enable it. For example, virtual mentorship programs might be used to connect HCWs, and technology that can aggregate and provide access to high-quality tacit knowledge might help grow a community-owned body of care expertise. To respect HCWs’ efforts at professionalization, technologies designed for these workers should avoid minimizing their skills through automation or reducing their control over their own practices. Finally, the home care context might indicate a need to design technologies for the collaborative co-production of emotional labor. While existing online collaboration platforms are usually focused on creating some informational artifact, an emotional collaboration platform might include ways to perform interpersonal emotional regulation and include affordances to express emotion and demonstrate active listening.

While HCWs are an increasingly important workforce in the United States, their peer support challenges may be decreasingly unique. Spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work has become increasingly common, even for professions which emphasize tacit knowledge and relational practices. Technology-enabled peer support may be one way to address issues of isolation, tacit knowledge sharing, and the politics of professional identity and mobilization for home care workers and other similar distributed workers.

- Awarded a Recognition for Contribution to Diversity & Inclusion.

- Published in the Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (CSCW).